In 2024, the ruling parties of several Southern African nations – Botswana, Mozambique, Namibia, and South Africa – were shaken by rapid shifts in voting patterns that eroded their dominance. These elections may mark a turning point in Southern African politics, signalling the decline of long-standing liberation parties that have governed since decolonisation. Once unassailable, they now face growing discontent, particularly among young voters. The elections left these parties with two choices: reform and democratise to address popular demands, or rely on institutional manipulation to maintain power.

The recent history of Southern Africa has been shaped by a liberation legacy that has its origins in the region’s delayed decolonisation and the ruptures caused by apartheid South Africa. The ruling parties of several Southern African nations – Botswana, Mozambique, Namibia, and South Africa – appeared largely unassailable until 2024, when they were shaken by rapid shifts in voting patterns that altered ruling party dominance across much of the region.

Remarkably, Botswana experienced its first change of government since it gained independence in 1966, and South Africa’s ruling African National Congress (ANC) fell below 50% of the vote for the first time since 1994. In Namibia, the South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) was pushed closer than ever before to losing its majority, securing only 58% in the presidential vote and a narrow 53% of the vote in the parliamentary elections. In Mozambique, strong anti-incumbent sentiment created expectations of a significant drop in support for the ruling party and sparked a months-long political crisis. Protesters took to the streets, and security forces responded with a widespread crackdown, resulting in the deaths of over 300 people. These events mark a turning point in Southern Africa, signalling what may well be the beginning of the end of liberation politics and a stark new set of choices for ruling and opposition parties alike.

This article discusses these shifts and the potential that they might provide to presage a new kind of politics in the region. It argues that the 2024 elections have left the old liberation parties of Southern Africa with two options: they can either reform and democratise, paying greater attention to citizen demands and the increasingly urgent need to tackle the region’s deepening inequality, or they will have to rely more on coercion and repression, which will further erode their legitimacy.

The acceptance of the election results by the region’s historic ruling parties demonstrates a level of political maturity and responsibility – a positive development for Southern Africa. As the balance of power shifts from liberation parties towards new opposition-led governments, we can anticipate an increase in coordination among opposition parties across the region. This, in turn, could gradually lead to a move away from the “quiet diplomacy” that characterised liberation movement solidarity in the region during the 1990s and 2000s.

Ageing liberators, youthful voters

Since the region’s delayed decolonisation between the 1970s and 1990s and the end of white settler rule, most of Southern Africa has been governed by dominant party regimes that can largely be characterised as “liberation parties”. A range of factors account for this dominance, some relatively democratic, others much less so. The “liberation party” is a specific subtype that can be democratic, authoritarian, or somewhere in between. Liberation parties claim legitimacy on the basis of having “liberated” the nation from tyranny, and they continue to assert this legitimacy at every subsequent election. Of the four nations discussed in this paper, Botswana is the only one to have been decolonised in the 1960s without a violent war of liberation. Nonetheless, ruling parties in Botswana, as in South Africa, Mozambique and Namibia, have conflated the party with the nation, presenting themselves as the parties of liberation and national identity. For decades, this culture has hindered the emergence of robust and stable party systems across the region, restricted political pluralism, and prevented the growth of strong opposition parties capable of holding incumbents to account.

Liberation politics always has an expiry date. As observed in Uganda, with each passing year, there are more young voters with no firsthand experience of what came before, and who are increasingly unwilling to accept excuses for poor state performance. Some ruling parties, for example, in Zimbabwe and Uganda, increasingly resort to repression when liberation credentials lose their appeal at the ballot box, or when a new generation enters the electorate for whom the liberation history is less salient. One legacy of violent political struggle and its clandestine politics is that liberation parties often have close ties to the post-liberation military and intelligence establishment and exhibit a tendency towards hierarchy and political centralism. Especially when political leaders have cut their teeth in the security forces, the distance from the politics of liberation to the politics of repression is not that great.

Most serving liberation party leaders and presidents are relatively elderly, with the pre-election leaders of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, and Mozambique all well into their twilight years.¹ In contrast, in 2024 the proportion of the electorate aged 18 to 34 years old was 57% in Mozambique, 53% in Botswana, 50% in Namibia, and 42% in South Africa. While the most pressing concerns for young voters are unemployment, continued poverty, the poor state of the economy, and high inflation, liberation parties have increasingly become associated with public sector corruption, high levels of personal enrichment for the politically connected, and inadequate service delivery. According to the Global Youth Participation Index (GYPI), across all four nations, young people tend not to be included in the political process, with very few represented in the decision-making structures of political parties or in parliament.

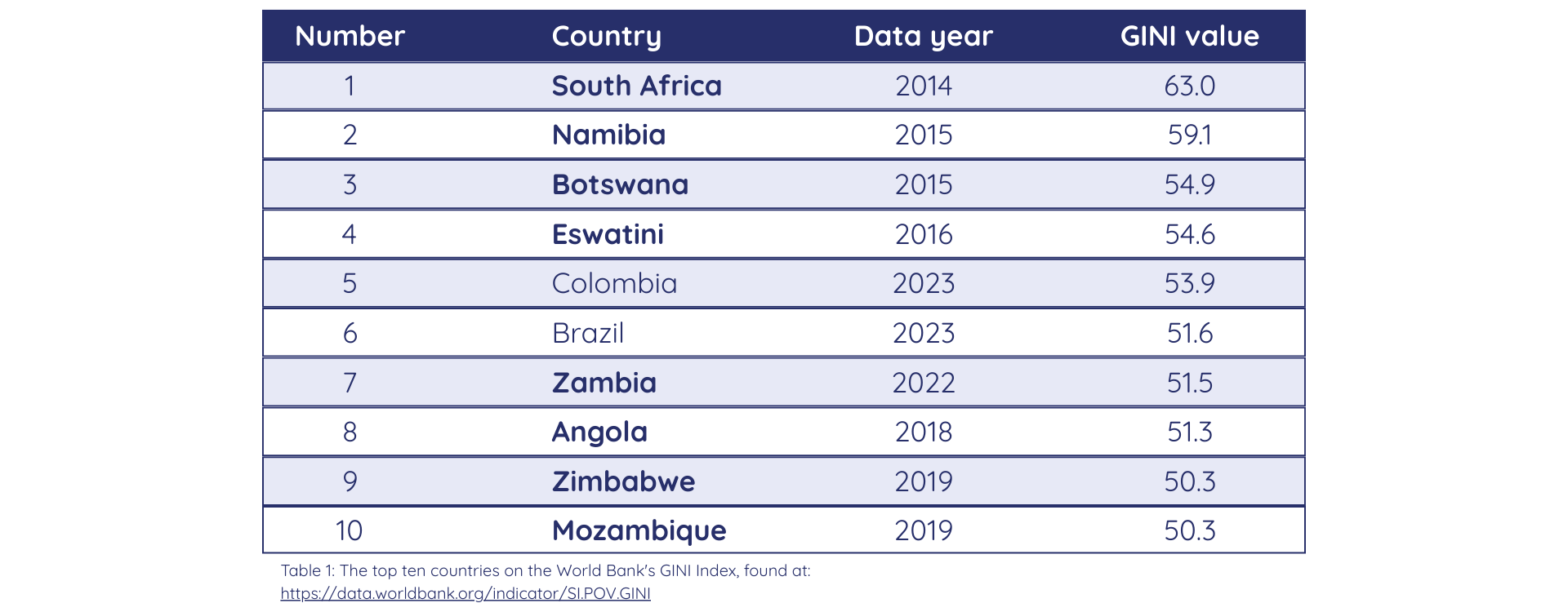

Southern Africa is by far the most unequal region in the world. The top ten countries on the World Bank’s GINI coefficient index – which measures inequality or the gap between the country’s richest and poorest citizens – contain eight of the Southern African region’s ten countries. Lesotho (20th) and Malawi (63rd) are the only two countries in the region that are not in the world’s top ten.

As noted by Oxfam, unchecked inequality poses systemic risks: it destabilises democracy, obstructs poverty alleviation and economic progress, intensifies the climate crisis, entrenches gender and intersectional injustices, and undermines the rights and dignity of ordinary people. This crisis has the potential to destabilise the entire region and requires urgent action by responsible and responsive governments if it is to be averted.

2024’s ‘super elections’ year

South Africa’s 2024 election results signalled the first major shift in the region, as the May election saw the ruling ANC party fall below the 50% threshold needed to appoint the president and form government unilaterally. The result humbled Cyril Ramaphosa’s ANC, which had to broker a new Government of National Unity – the first national-level coalition since the transition from apartheid. It includes the largest opposition, the centre-right Democratic Alliance (DA), and nine smaller parties, and was widely seen as the start of a new era of coalition governance. While decision-making is often slow, the coalition government in South Africa has so far increased public trust in governance. In the first six months, the approval ratings of the two major parties improved by over 10%. It has also been good for the public, as the animated debate over the ANC’s mooted rise in VAT illustrates. It was a significant achievement that the ANC was willing to respect the wishes of the electorate, setting a precedent for the rest of the region’s liberation parties.

In October of the same year, Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) was unexpectedly removed from power after 58 years by an opposition grouping, the Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC), led by Duma Boko. The UDC secured 36 of the 69 National Assembly seats, while the BDP won only four seats, having previously held 38 seats. The runner-up, the Botswana Congress Party (BCP), became the official opposition, with 15 seats. This represents a substantial rejection of the BDP, which had become increasingly unpopular as a result of high youth unemployment, food price inflation, and growing corruption. Overall, the election was well-conducted, with relatively few concerns raised by observer groups. But what stood out was the gracious handover of power by President Masisi, who had been accused of becoming increasingly autocratic. In a call to his successor, he said, “From tomorrow, … I will start the process of handover. You can count on me to always be there to provide whatever guidance you might want… We will retreat to being a loyal opposition.” Boko, a human rights lawyer and Harvard Law School graduate, faces significant challenges. Despite inheriting a government with severely limited finances, he has made bold – and sometimes populist – promises. Another challenge will be keeping this umbrella party, a collection of relatively disparate groupings, together.

Mozambique’s election the same month was very different. It was marred by serious allegations of fraud and maladministration, leading the opposition to challenge the results. Initial results released by the electoral commission gave the 47-year-old candidate of the ruling Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (Mozambique Liberation Front or Frelimo), Daniel Chapo, 70.7% of the vote. The country’s Catholic bishops spoke of ballot-stuffing, while EU election observers noted “irregularities during counting and unjustified alteration of election results”. In protesting the results, the opposition Podemos and its presidential candidate, Venâncio Mondlane, called for a boycott, after which two of its leaders were assassinated on the streets of Maputo. Weeks of protests followed, accompanied by a brutal crackdown by security forces, resulting in thousands of arrests, at least 3,000 fleeing to neighbouring countries, and over 300 people killed. After an opposition challenge, the country’s Constitutional Council upheld Chapo’s victory, although his winning percentage was revised down to 65%. Chapo, the first president born after independence from Portugal (1975), represents a generational shift for Frelimo; however, the circumstances of his election have undermined his legitimacy in some quarters, particularly amongst young people. The official results are widely regarded as implausible, which affects public trust in both the government and the electoral commission, reinforcing the idea that Frelimo cannot be removed through the ballot box. Nearly three months of protests followed the Constitutional Council’s decision, which many have called a ‘youthquake’, reflecting the growing dissatisfaction among young people with the rule of liberation parties.

The last of the region’s 2024 elections in Namibia on 27 November saw a chastened SWAPO manage to retain the presidency with the election of Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah (known as “NNN”), the country’s first female head of state and the first elected female head of state in Southern Africa.² This was not the first tough election that SWAPO had faced, as the polls in 2019 showed the first signs of a changing electorate and unfavourable political headwinds. With the ruling party’s trust and credibility, founded on its liberation history, beginning to wane, the slogan “SWAPO is the nation, and the nation is SWAPO” is starting to sound hollow.

Namibians born after independence now make up half of the country’s population, with a median age of 21, just a few years older than the legal voting age of 18. With the government tainted by the ‘Fishrot scandal’, the largest corruption scandal since independence, young people feel frustrated by persistently high unemployment rates. The choice of Nandi-Ndaitwah undoubtedly helps distance the party from the 2021 scandal, as she is seen as having an unblemished record. She is regarded as having ‘personified integrity’, which makes her commitment to root out corruption in the party credible. The survival of SWAPO will depend on its willingness to change deeply-rooted habits.

The long tail of liberation politics

The experiences of Mozambique and South Africa highlight the two different paths available to liberation party governments faced with challenges to incumbency: “reform or repress”. They can either address the concerns that make them unpopular with young voters or rely more heavily on institutional manipulation and coercive strategies to maintain power. Cyril Ramaphosa seems to be committed to reform, though the ANC often appears to be an unwilling participant in the unwieldy national-level coalition. To win back voters, the ANC must undertake serious and systematic reform, addressing poor service delivery and the jobless growth of recent decades. But despite their political challenges, the ANC does not seem to be trying to maintain its position through coercion, suppression of the opposition and electoral manipulation.

Mozambique has taken a different path. Frelimo’s decision to present a fresh face, the relatively unknown Daniel Chapo, was clearly intended to attract young voters. Chapo is believed to understand that Frelimo needs to reform and open up democratic space, but his selection as presidential candidate is said to be the result of a compromise by the ruling party’s old guard, rather than evidence that the party is committed to a change of approach. Former President Filipe Nyusi will remain in post as Frelimo’s Secretary General until 2027, and he is backed by a group of hardline former generals with substantial financial interests to protect. This suggests that unless the balance of power radically shifts within the party, the election of a young president will not necessarily signal a change of direction for the old liberation party. A new face is unlikely to be enough to convince Mozambique’s young electorate. Although it appears that the government is investigating the excessive use of force by police and intends to hold the former police chief accountable, the new president continues to refer to the young protesters as criminals, which seems certain to further antagonise those youths who are calling for change. Radical reforms are needed for Mozambique to shift direction, but it is unclear whether Chapo and Frelimo are willing to take a road towards greater democracy and accountability.

As Roger Southall wrote over a decade ago, we are reaching the end of an era in Southern Africa. As liberation parties lose power across the region, it is by no means clear which of the two paths they will take: reform or repression. Although Namibia is often cited as one of the region’s most effective democracies, Henning Melber argues that its political culture is not truly democratic, but is marked by ‘democratic authoritarianism’ and a lack of respect for dissenting opinions and for non-SWAPO forms of patriotism. He argues that, given the predominating political culture within SWAPO, a truly democratic breakthrough in Namibia is an “unlikely development in the near future”. It is not clear what will happen when SWAPO loses power, but the experience of South Africa suggests that the personality and personal convictions of whoever is president will be significant in determining the shape of the future.

Facing forward?

Having more opposition parties in power is likely to significantly affect opposition funding and support across the region, and will weaken the strength of liberation party ties, which have in the past prevented meaningful action against countries that violate regional norms within the Southern African Development Community (SADC). The fact that opposition parties have long been among the region’s least trusted institutions has impacted their ability to win people over to their cause. But the increasing connections between regional opposition parties – some of which are now in government – have helped to boost their profile, capacity, and ability to attract funding. Tensions emerged between Zimbabwe and Zambia following the 2021 election of the United Party for National Development (UPND) over the party’s close relationship with Nelson Chamisa’s Citizens Coalition for Change (CCC). Liberation solidarity has been blamed for the region not taking a tougher stance against governments that oppress their people, steal elections, and reject accountability. The strong stance taken by the Zambian head of the Southern African Development Community’s (SADC) observer mission to the 2023 election in Zimbabwe was widely seen as having breached norms of “liberation solidarity” and the quiet diplomacy that was characteristic of the region. With more opposition parties in government, this trend is likely to continue, and may give cover for more regional leaders to break ranks and call out misgovernance and problematic elections.

But at the national level, even though more competitive elections should be good for electorates and democracy, not all of the region’s opposition parties are committed democrats. A shift to the opposition will not necessarily mean the consolidation of democracy. For example, Mozambique’s Venâncio Mondlane has a penchant for the far right and authoritarian populists in Europe, Brazil, and the US. Believing himself to be divinely chosen to lead Mozambique, he is clearly not a firm believer in party institutionalisation.³ It is by no means clear that an electoral victory for Mondlane would result in greater democracy. The South African uMkhonto weSizwe Party (MKP) of former president Jacob Zuma operates more like a family business than a political party, and shows signs of being an anti-system party. The premise for the DA establishing South Africa’s Government of National Unity was specifically to block a “doomsday coalition” of the MK and the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) with the ANC. Whether the current national coalition survives, and how it performs on key governance questions, is likely to have a crucial impact on future voting behaviour and the continued relevance of Zuma’s MKP.

While it is important not to equate an opposition victory with an inevitable march towards greater democracy, research does suggest that rotations of power can serve as important signifiers to voters about the value of voting, and also create political room for institutional strengthening, which may have a longer-term impact on democratisation.

Conclusion

The evolving landscape of ruling parties and power in the region may well signal the beginning of the end for liberation parties and the further strengthening of democratic norms in countries like Botswana and South Africa. For those liberation parties still in government, the writing is on the wall: they will either need to reform to meet the expectations of a younger and more demanding electorate or resort to greater coercion to hold on to power. In a shifting regional dynamic, with former opposition leaders increasingly in government, liberation parties can expect to face increased criticism and the possibility of isolation.

The consequences of these shifts for the region could be significant, including the breakdown of the liberation solidarity that made it difficult to hold leaders accountable for domestic human rights abuses and election fraud. What is clear is that the twin challenges of increasingly unequal societies and increasingly dissatisfied youth must be addressed if Southern Africa is to avoid a crisis.

¹ In 2024, Mokgweetsi Masisi (Botswana) was 63, Filipe Nyusi (Mozambique) was 66, Cyril Ramaphosa (South Africa) was 71, and Hage Geingob (Namibia, died just before the polls) was 82.

² The region’s only other female president, Joyce Banda, became president in Malawi following the death of President Bingu wa Mutharika and was never democratically elected.

³ Venâncio Mondlane began his career in MDM, shifted to Renamo, and then to the Democratic Alliance Coalition before finally being backed by Podemos in 2024.

Author

Dr Nicole Beardsworth is a lecturer in Politics at the University of the Witwatersrand and an honorary research fellow in Politics and International Studies (PAIS) at the University of Warwick. She holds a PhD in Politics from the University of Warwick, an MA in International Relations from the University of the Witwatersrand and an MSc in African Studies from the University of Oxford. Her PhD research focused on opposition parties and electoral coordination in Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Her broader research is on the history and politics of sub-Saharan Africa, with a focus on political parties, governance, democratisation and elections in Southern and Eastern Africa. She is a regular writer for several academic blogs and newspapers and tweets from @nixiib.

This publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union as part of the AHEAD Africa project. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.