Since the early 2010s, several initiatives – such as V-Dem’s Democracy Indices and International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy Indices – have been launched, and track and monitor the state of civic space around the world. Today, policymakers, activists, and researchers have access to hundreds of data points to better understand democratic trends. However, it remains unclear how effectively these tools have helped democracy support actors respond to these developments. As a growing number of governments around the world impose restrictions on civil society, these monitoring tools have become more essential than ever.

The international community, in response to the responsibility to protect, strengthened its conflict-related early warning analyses and capabilities in the early 2010s. This led the democracy community to call for expanding this work to include human rights violations. The clear trend of worsening democratic freedoms, noted by organisations like CIVICUS and Freedom House since 2018, has prompted several recent initiatives to monitor and warn about the state of, and changes to, civic space worldwide. Since then, the EU and other donors have invested significant resources in developing early warning systems to help diplomats, donors, philanthropists, researchers, and civil society actors assess and respond in real time to democratic developments.

Have these tools helped, or do they have the potential to help the international democracy community better understand and respond to positive and negative changes? Are these tools still fit for the new era of funding cuts in assistance and a shift towards geopolitical interests?

What are the strengths and weaknesses of these tools?

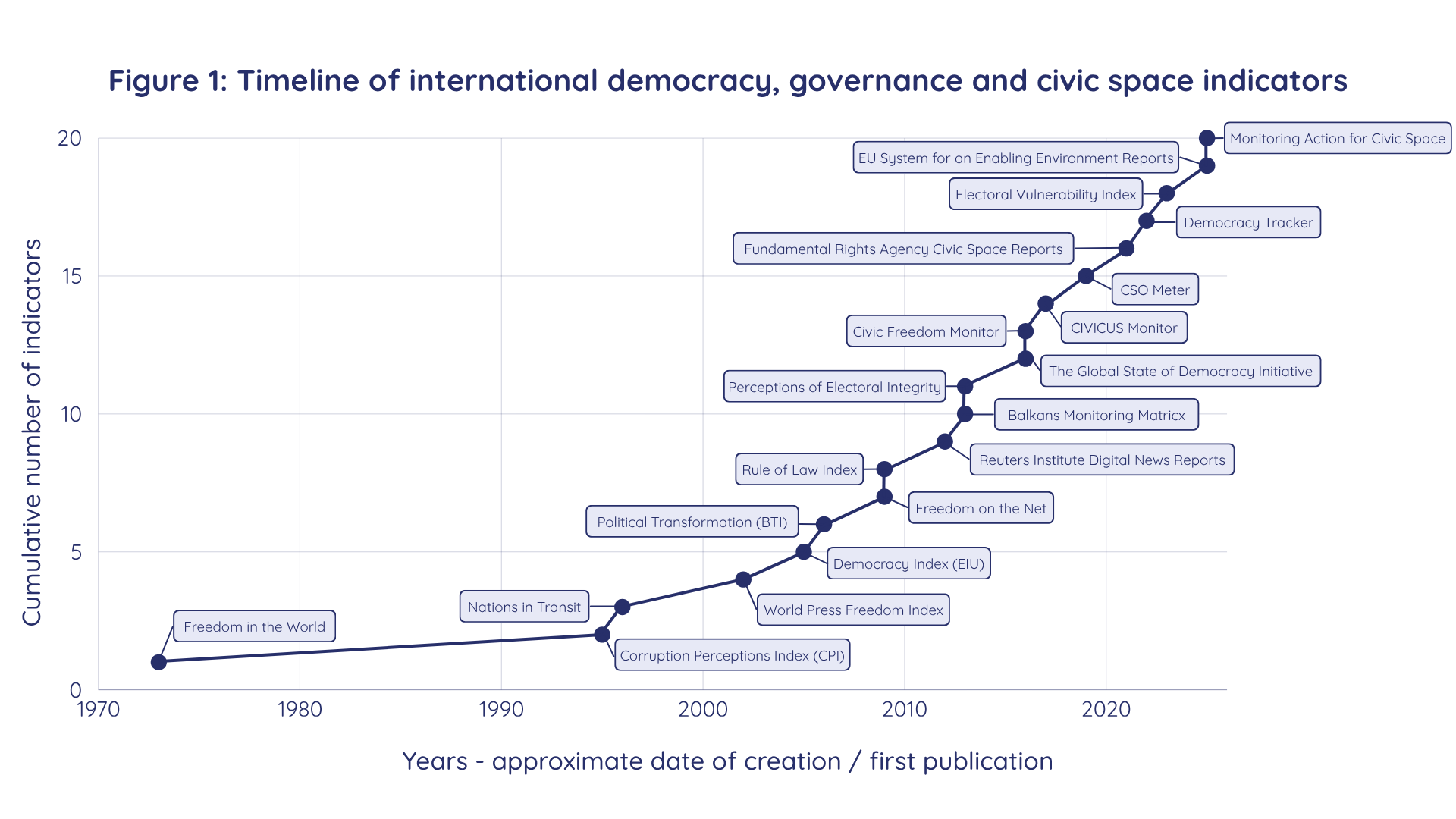

Existing tools provide in-depth and comprehensive information on democracy and civic space, aggregating information contained in news sources, reports, and expert information. Work started early in the 1970s with Freedom House’s Freedom in the World Index, followed by exponential growth in governance and democracy indicators (see figure 1) in the civic space field. The CIVICUS Monitor has been joined by more recent newcomers such as the European Center for Not-for-Profit Law’s (ECNL) CSO Meter and Monitoring Action for Civic Space (MACS), as well as the EU System for an Enabling Environment (EU SEE). While these tools are implemented by civil society, others are produced by intergovernmental bodies, such as International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy (GSoD) indices and Democracy Tracker, or the EU Fundamental Rights Agency’s (FRA) annual update on civic space in the EU and in candidate countries.

International IDEA’s GSoD indices and Democracy Tracker, as well as another tool—Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) — excel at quantitative, cross-country identification of trends and at retrospective diagnosis of democratic backsliding—that is, the gradual erosion of democratic institutions, norms, and freedoms over time. They can detect slow-burning processes like institutional capture or the weakening of democratic checks and balances – often before mass protests or legal crises become visible – and they have methodological credibility. They identify clear patterns in autocratisation, with progressive institutional weakening, attacks on democratic institutions, and targeting of individual civil society organisations —all of which indicate a dangerous slide downwards.

For example, Hungary’s democratic backsliding was clearly visible in V-Dem data from 2011 to 2012, starting with a decline in media freedom and judicial constraints on the executive, well before the European Parliament formally declared a “risk of serious breach of EU values” (Article 7) in 2018.

At the same time, these tools are less suited to detecting sudden events such as coups or emergency decrees in real time because annual coding and aggregation introduce a delay. Interpretation also requires numerical analysis and separating noise from meaningful trends.

Event-oriented monitors (IDEA Democracy Tracker, CIVICUS, EU SEE, MACS, CSO Meter), on the other hand, are better at flagging discrete turning points or legal and operational changes that can precipitate rapid deterioration. Significant vetting is still needed to ensure the information is correct, unbiased, and properly contextualised. Many indices indeed can flag a “risk” or deterioration that later plateaus or reverses; interpretation requires triangulation using legal texts, domestic reporting, and on-the-ground corroboration. Freedom House’s index is highly visible and effective at detecting sharp declines in liberties tied to events such as states of emergency or coups and communicating them widely. This is useful for rapid political narratives, though it offers less detail on legal technicalities affecting civil society organisations compared with specialist civic space monitors.

CIVICUS Monitor, CSO Meter, MACS, and EU SEE are practitioner-oriented early warning systems focused on civic space, such as laws, administrative practice, and repression. They excel at near-real-time alerts and actionable signals for donors and advocates. For example, CIVICUS warned of the possible reintroduction of a repressive NGO law in Kyrgyzstan in September 2022, which was then published by the government in November.

These tools, however, vary in geographic scope and indicator standardisation, which is expected as they are civil society-led and depend on the methodologies developed by each set of participants. When they use scoring bands, these can be considered “coarse” (open → closed) and may mask differences within categories. Reliance on civil society reporting capacity also means coverage can vary by country, and on the quality of their sources. As some have a high legal or technical focus, such as registration rules, funding controls that strongly impact civil society specifically, they can provide precise indicators that help detect civic space deterioration and are useful for detecting “pathways” of restriction.

FRA’s EU civic space reporting is authoritative for patterns within EU member states and has successfully signalled emerging threats, but it operates on a slower annual consultation cycle. Its Fundamental Rights Report and civic space inputs are crucial for intra-EU policy debates and are considered extremely credible in EU policy circles.

No single product, however, is perfect. The best “early warning” practice involves combining sources: global quantitative trend data (V-Dem, IDEA) for signal detection, alongside targeted civic space monitors (CIVICUS, ECNL, EU SEE, MACS) for fast, actionable corroboration.

Often, these tools cross-reference each other, avoiding duplication by producing new data while drawing on existing datasets to produce differing analyses. Around half of the GSoD indicators come from V-Dem, but it also produces primary data collected by the International IDEA’s voter turnout database. EU SEE uses CIVICUS Monitor and V-Dem data to cross-check EU SEE country-level analyses, produced by its researchers, with the data contained in CIVCUS and V-Dem indicators. It can thus concentrate on its added value in producing elements not covered by other mechanisms, such as indicators relating to public narratives on civil society, or civil society’s access to sustainable funding and resources.

Do these tools provide the necessary information for policy change?

Anyone, from citizens to activists, advocates, researchers, and decision-makers, can now access hundreds of data points and analyses to help them understand developments in the democratic space worldwide. Some of these indices clearly indicate that their goal is to produce tools for advocacy, others do not. But is the information produced ready to be consumed by decision-makers or the media and actionable for other civil society partners?

Stated objectives range from V-Dem’s wish to help better conceptualise and monitor democracy, to GSoD’s and Democracy Tracker’s aim “to provide evidence-based, balanced analysis and data on the state and quality of democracy, contribute to the public debate and inform policy interventions to strengthen democracy” and “serve as a timely and policy-directed tool for monitoring events and alerting audiences to their potential impacts on democracy and human rights”. CIVICUS Monitor has the even more ambitious goal of influencing “decisions that matter to people’s lives”, connecting citizen action to make it more robust and effective, and helping civil society carry out its work.

ECNL and partners use the CSO Meter to produce regional reports analysing trends, and in-depth reports on issues such as the “Impact of anti-money laundering and countering terrorism financing measures on non-profit organizations in the Eastern Partnership region”. Freedom House goes further and publishes reports, based on its index, with full policy recommendations. EU SEE is even more innovative, monitoring changes and shedding light on critical trends in the enabling environment so that civil society, governments, and stakeholders receive actionable insights, while being linked to a support mechanism that delivers flexible and timely financial assistance to civil society organisations that can promptly act.

It is challenging to ensure that all potential target audiences, ranging from the public to civil society organisations, researchers, and decision-makers, receive the information in the most suitable format for them to understand, digest, and utilise. Effective change occurs when all these actors use the data to advocate for action, develop policies or interventions, and monitor their implementation and impact. FRA involves civil society partners in information gathering through online consultations, which have strengthened the ownership by citizen groups of its resulting reports. CIVICUS promotes the civic space monitor internationally through a blend of high-level advocacy, media engagement, strategic events, and knowledge tools. For example, it engages directly at high-level events at the United Nations in Geneva and New York, including the Human Rights Council (HRC) sessions and Universal Periodic Review (UPR) processes.

There is ample evidence that civil society, decision-makers, and thought leaders are gathering this information and using it for their own monitoring, policymaking, and advocacy. However, strong, direct causal evidence, such as the EU statement: “we acted because civil society organisation X alerted us”, is rare in public documents. The EU typically frames decisions using legal and political reasoning rather than attributing action to a single advocacy trigger, meaning that indirect evidence must be found. An example of this indirect referencing can be found in the Commission Staff Working Document for the Republic of Moldova 2023 Report, which states that “CSO monitoring in 2022 highlighted several gaps hindering the transparency of decision-making and public participation in Parliament”, while the ‘CSO Meter: A Compass to Conducive Environment Moldova report 2022’ contains a detailed analysis of the challenges for civil society organisations to be consulted in the elaboration of laws by that body.

The FRA reports on civic space and International IDEA’s GSoD indices are widely cited by key standard-setting bodies such as the European Commission and Parliament, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), as well as researchers, NGOs, and think tanks. Similarly, CSO Meter work has been used by the European External Action Service (EEAS), OHCHR, academia, think tanks, and civil society organisations. However, it is less certain and more difficult to track whether the recommendations for action are also being adopted alongside the data.

Case study: Philippines

1) Civil society monitoring alerts about restrictive COVID-19 measures (April 2020)

The CIVICUS Monitor COVID-19 brief (1 April 2020) documented the Philippines’ emergency measures (the Bayanihan to Heal as One Act and enforcement practices) and warned that provisions penalising “false information” and the highly militarised enforcement of the lockdown risked curtailing freedom of expression and civic space. NGO/monitor reporting (CIVICUS, Human Rights Watch, and others) documented restrictive emergency powers, arrests of critics, and provisions criminalising “false information” during the lockdown (March–April 2020). These were immediate, on-the-ground alerts and country notes.

2) OHCHR/UN reporting that draws on civil society information (June 2020):

According to an OHCHR press release (4 June 2020), the UN Human Rights Office published a report (A/HRC/44/22 Philippines) detailing “widespread human rights violations and persistent impunity” in the Philippines and highlighted concerns including the use of emergency powers, restrictions on expression, and harassment of human rights defenders. OHCHR explicitly notes that the report is based on information that includes civil society submissions.

3) Follow-up/technical cooperation and official domestic acknowledgement:

The statement by the Commission on Human Rights of the Philippines welcomed the OHCHR report on the country’s human rights situation, highlighting the ongoing engagement and technical cooperation between the Philippines and OHCHR.

All tools need to combine qualitative and quantitative data to avoid reducing complex experiences to numbers alone. Storytelling and case studies are also key to communicating impact and connecting with decision-makers on an emotional level.

Many of the above operators have dedicated operations streams to mobilise attention, from communications frameworks that amplify their voice, to advocacy staff who reach out to targets, and events that present conclusions for debate with interested audiences. EU SEE uses public meetings to promote its work, methodology, and recommendations, while also showcasing the organisations carrying out research in each of the 86 countries where it operates. It publicises its reports through dedicated webinars for policymakers and writes articles that are more accessible to the media and wider public.

Carrying the EU name or receiving EU funding can help in getting EU institutions to share their information within their walls, and over time, generating interest and support from the European Parliament and Council, the same way ProtectDefenders.eu has been able to, as a flagship project. The EU programming document for CSO Meter clearly states that one of its roles is to “issue early warning reports on possible closures of civic space and provide feedback for EU political reporting and assessments”. The EU Thematic Programme for Civil Society Organisations Multiannual Indicative Programme 2021–2027 mentions that “by generating and disseminating timely and meaningful information and analysis, including early warnings, actions under the system [the Monitoring and Engagement System for an enabling environment, subsequently named EU SEE] may inform EU wide actions for democratic governance, civic space, and an enabling and accessible environment for civil society”. FRA and IDEA, as inter-governmental bodies, obviously have privileged access to member states’ governments, which they use to organise “high-level dialogues and consultations with EU decisionmakers to facilitate evidence-based discussions on the fundamental rights implications of proposed policies”.

Different audiences also have different needs, capacities, and reaction times. Some actors are best placed for rapid reaction to emerging crises, such as diplomats, philanthropic actors, or civil society, and others for more structural democratic change, such as cooperation specialists.

Are these monitoring mechanisms fit for purpose in a changing world?

The shrinking space for civil society worldwide makes these tools more crucial than ever. Decision-makers need to track the spread of restrictive policies, funding, and narratives in real time. Early warning can help mobilise diplomats, funders, and NGOs around strategies to counter threats, identify trends, and gather and share information that helps prevent deterioration or prepare for worsening situations in countries.

For now, it is unclear whether the data produced by monitoring tools allows all these stakeholders to react in time by catching the earliest possible signs of deterioration, or indeed of opening. News travels fast, and stakeholders are often already aware by the time researchers have cross-checked the information. It might be a myth that there is a clear, identifiable, and unmistakable “early” warning event that sets everything in motion.

Nevertheless, governments increasingly copy each other’s repressive tactics, which follow similar patterns and help onlookers spot the telltale signs of measures to come. Anti-civil society narratives also seem to follow a playbook, often starting with attacks on gender, environment, or anti-corruption human rights defenders. This makes it possible to prepare other organisations for the inevitable spread of these narratives across societies and countries.

EU SEE was able to warn the EU early in September 2025 about the Nepal protests, identifying the first signs of tension and helping the institution better prepare. Diplomats reported that alerts from outside the capital region provided particular added value. They are usually well briefed on the political, social, and civic happenings in and around government and in the major cities, maintaining strong connections with human rights defenders, major civil society organisations, and political actors, and subscribing to news scraping services. However, developments outside of these circles are less within their purview.

In these times of deep funding cuts in democracy assistance within countries and across borders, civic and democratic space assessments can help donors target their funds on preventing further deterioration, mobilising civil society, and responding as fast as possible. Yet, many donors do not always have the necessary flexibility, appetite for risk-taking, and, increasingly, political priority to support actions that would allow civil society to organise and respond.

Open questions remain about how new and predominantly investment-based foreign funding strategies, carried out via development and financial institutions, will prioritise an enabling environment for civil society as a good governance guarantee, and which standards will apply in this area.

For these tools to remain effective, the international donor community must rediscover and clearly articulate how civic space is crucial for ensuring investment projects are well designed and impactful. Democratic institutions that consult civil society and allow it to fully play its accountability role can better respond to community needs. Without this, civil society will find it increasingly difficult to operate and provide information on the state of civic space. Civil society must also receive support to develop its capacity for data collection and analysis, including the use of artificial intelligence, as well as for advocacy, which is often overlooked and particularly threatened by foreign agent laws.

Funding cuts, particularly the recent US ones, may imperil certain monitoring tools that were used as references for civic space and democracy monitoring. The question of which tools will be discontinued is key today and requires examination by the monitoring and donor community. While these tools are not in competition, better donor coordination, in dialogue with the operators, can ensure that complementarity between existing tools is maximised. The question of rationalising these tools might arise—there are many data tools with non-standard methodologies that could otherwise better complement each other if donors developed a more coherent approach. The plethora of generalist data instruments should also be accompanied by more specialised ones, among them the Freedom on the Net index, and others which are quite rare, if not absent, such as one tracking negative public discourse on civil society.

Common bases between the tools, such as shared definitions and frameworks, could help with their interoperability, for example, civic space and democracy indicators. Organisations and initiatives with convening power, such as FRA, EU SEE, and IDEA, play a vital role in the monitoring and advocacy ecosystem. Their ability to bring stakeholders together will be key to building alliances, trust, and coherence, sharing practices, and improving the overall system.

Donors’ civic space support mechanisms need greater adaptability through rapid reaction to events, or alternatively, through core funding of civil society organisations that allows these to respond flexibly to fast-changing situations. The EU can also further strengthen coordination initiatives such as Team Europe Democracy to ensure available funds among member states for reacting to civic space and democratic developments are well synchronised, allowing more flexible donors to react first.

Information management systems that better integrate monitoring tools into decision-makers’ full range of action, from diplomacy to funding, will help increase data uptake. Clear, detailed indicators can also help donors and initiatives alike develop better success metrics and performance measurement. Internal coordination between aid and foreign policy departments is crucial in an era of diminishing budgets.

The public nature of some monitoring mechanisms can also help “name and shame” repressive actors and focus attention on their strategies, although these actors are increasingly defiant in the face of international scrutiny. This approach also carries heavy risks for the organisations conducting this work as it leaves them exposed to accusations of being foreign agents, traitors, spreaders of disinformation, or threats to national security, cultural values and sovereignty, or being politically biased and playing into the hands of the opposition. This makes translating the value of monitoring and alerting into joint strategies and action more difficult, as civil society and movements are hampered in their capacity to join forces and act.

Donors and diplomats are also increasingly hesitant to voice concerns or act against civic space violations amid a rising tense geopolitical landscape. They face mounting backlash from host governments for publicly addressing “internal matters” and are often accused of the same charges as civil society organisations: playing politics, importing foreign values, exhibiting bias, and acting as malicious foreign agents. This can create discomfort with internal pressures to finalise deals on migration, critical materials, or significant investments. Additionally, trends of democratic backsliding or civic space restrictions at home can discourage taking strong stances on these issues internationally.

The international community must rediscover the strength to support human rights, civil society, and democratic standards, to speak up in their favour, and explore new narratives and support systems together with civil society, to ensure these values are preserved. Monitoring mechanisms have value in helping their audiences adapt and evolve in an ever-faster-paced world by helping share not only information but also connections, thinking, and strategies. It is only by learning from each other that civil society can adapt to ever-changing and evolving threats.

Authors

Emma Achilli is the Strategic Advisor on Civic Space at the European Partnership for Democracy (EPD), working on the EU SEE (System for Enabling Environment for Civic Space) project. Before joining EPD, she was head of the EU office for Front Line Defenders, and an EU official for 15 years (Commission, Parliament and Council) working on human rights and development policy, diplomacy, and programmes. She has also been an independent consultant for several years, working for Open Society, ProtectDefenders.eu, ENNHRI, Amnesty International, the EU and others. She holds a Masters in Human Rights, one in Development Studies, and a degree in Economics from the London School of Economics.

Vincent Labrevois-Simonetti is a Research & Programmes Officer at the European Partnership for Democracy (EPD). His main work consists of overseeing EPD’s scientific contributions to the EU SEE (System for Enabling Environment for Civic Space) project, as well as diverse internal workstreams and initiatives with EPD members ranging from methodological development (Monitoring and Evaluation, Political Economy Analysis) to various IT and AI related experimentations and projects. A political economist by training, he has held a variety of roles in a wide range of fields including citizen participation, consulting in the civic tech sector and humanitarian research. These experiences have enabled him to develop a complementary set of skills in project management, workshop design, data analysis and research.

The authors work for the EU System for an Enabling Environment for Civil Society (EU SEE) project led by Hivos.

This publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

Photo credit: © Martin Sanchez, unsplash