There is a pressing need to address how citizens’ assemblies should navigate the complex world of politics to drive meaningful change. While governments seek radical reform, citizens’ assemblies are positioned as a key solution within deliberative democracy. These assemblies offer consensual policies, citizen mobilization, and intergroup solidarity. Yet, their impact on policy change has been inconsistent. To remedy this, the article proposes a new theory of change, involving diverse tactics, active citizen engagement, and broadening the scope of assembly influence.

If citizens’ assemblies are to achieve significant change, they will need to step into the political fray and get real about how power and politics works.

There is a strong consensus that government is broken and needs a radical overhaul. Politicians of every stripe have promised a “new politics” in an attempt to translate anti-political sentiment into votes. But there has been a lack of practical details about how to move beyond rhetorical tropes.

According to the OECD, there have been over 300 deliberative processes across the world in recent years and formats like citizens’ assemblies have emerged as a key prospect for this new politics. That is why activists, academics, and even officials are pushing for more of these.

Citizens’ assemblies are seen as an answer to how to fix the “governance chamber” bit of the political system. The momentum behind them is in effect a global experiment in how to reimagine our governance chambers. And they are supported by an ever-growing field of academics, practitioners, and civil society organizations that generate the practical know-how the politicians’ promises previously lacked.

Citizens’ assemblies, which have been mostly organized in rich countries in the Global North, can generate consensual policies that are the result of collective intelligence informed by lived experience and evidence. They are perceived by the public to have high legitimacy as they consist of representative samples of people, not politicians (in whom trust is low and declining in most countries). They also mobilize citizens to take action and to engage in politics and society more generally, and they generate understanding, respect, and solidarity between diverse social groups as a counterweight to hyper-partisanship and disinformation.

However, the impact of citizens’ assemblies on policy and practical change is patchy at best. Some advocates push for politicians to give them formal policy mandates, assuming that this is the best route to change. The most high profile example of this approach was France’s President Emmanuel Macron’s commitment to “not filter” any recommendations coming out of the country’s Citizens Convention for Climate. In practice, his government “filtered” heavily, as just one in ten of the recommendations were fully taken up by the government.

This focus on assemblies’ political mandates is divorced from an understanding of how change actually happens. The reality is that citizens’ assemblies have to embrace a wider suite of political tactics if they are going to achieve their promise of being a significant part of the new political apparatus. They need to become more political. And to do that, they need a new theory of change.

A New Theory of Change

A new theory of change for citizens’ assemblies must be guided by three core assumptions. First, governmental institutions will not implement all proposals by assemblies without external pressure. Second, citizens have significant power to effect change with or without institutional support. Third, there is a significant policy-action gap, meaning that policies do not always translate to effective action.

The first assumption means that it is not feasible to think in terms of neat linear political mandates, as politics works in a far messier and brutal way. It reflects the evidence that, even if they say they will, institutions will not implement all recommendations without external pressure, or at best they will cherry-pick or water down recommendations. This can be addressed by deploying insider and outsider strategies such as lobbying and campaigning to encourage action.

In the case of the Citizens Convention for Climate in France, industries mobilized against the citizens recommendations until “nothing much remained of the original ambition of the 150 citizens”. Support for citizens’ assemblies must not be politically naive, inadvertently providing democratic legitimacy for initiatives that do not make a real difference. This point is critical. Years of speaking to politicians about citizens’ assemblies have shown us that the majority do not think there is a serious democratic crisis. And why would they? They have committed their lives to making representative democracy work; they are in a way the ultimate political insiders. They tend to see citizens’ assemblies as just another lobby trying to get their attention, so it is no surprise that they do not listen.

The second assumption ensures that citizens are not framed as passive actors, which would deny them the great power they have. This is particularly important, as the scale of the current “poly-crisis” requires action from everyone. No institution, no matter how well resourced, can respond to the challenges without mobilizing millions of people to act. The Covid-19 pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis have taught us that all our actions count, whether it is social distancing, energy saving, or looking after friends and neighbors. And yet we have a crisis of what academics call self- and collective efficacy: people feel trapped and that there is nothing they can do in the face of such challenges.

We know that citizens’ assemblies can radically increase peoples’ efficacy, but only when people are framed as active agents of change and given the “scaffolding” required to act. This means framing assembly members as political actors: that is, training them to speak to the media and supporting them be advocates for the assembly. This was the case for France’s Citizens Convention for Climate and the Global Assembly for COP26, but it does not always happen. When it does not, there is a danger of replicating old power asymmetries, in effect making people’s sense of powerlessness worse.

Third, the policy-action gap tells us that citizens’ assemblies can generate change not only by pushing for specific policies but also by demonstrating a new governance model. There is unprecedented demand for a change in political system. For example, in a 2021 survey, there were big majorities in advanced economies for doing so dramatically; for example, 85 percent in the United States, 84 percent in South Korea, and 73 percent in France. There were also big majorities in France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States supporting the establishment of citizens’ assemblies and the idea that people, not politicians, should be allowed to decide what becomes law.

When the Global Assembly members issued their declaration at COP26, what made it stand out was the process that led to it. Citizens’ assemblies provide hope that it is possible to address the democratic crisis, creating spaces where people can innovate, learn, and demonstrate alternative forms of governance that illuminate a practical path toward a better democratic future.

Power Literacy

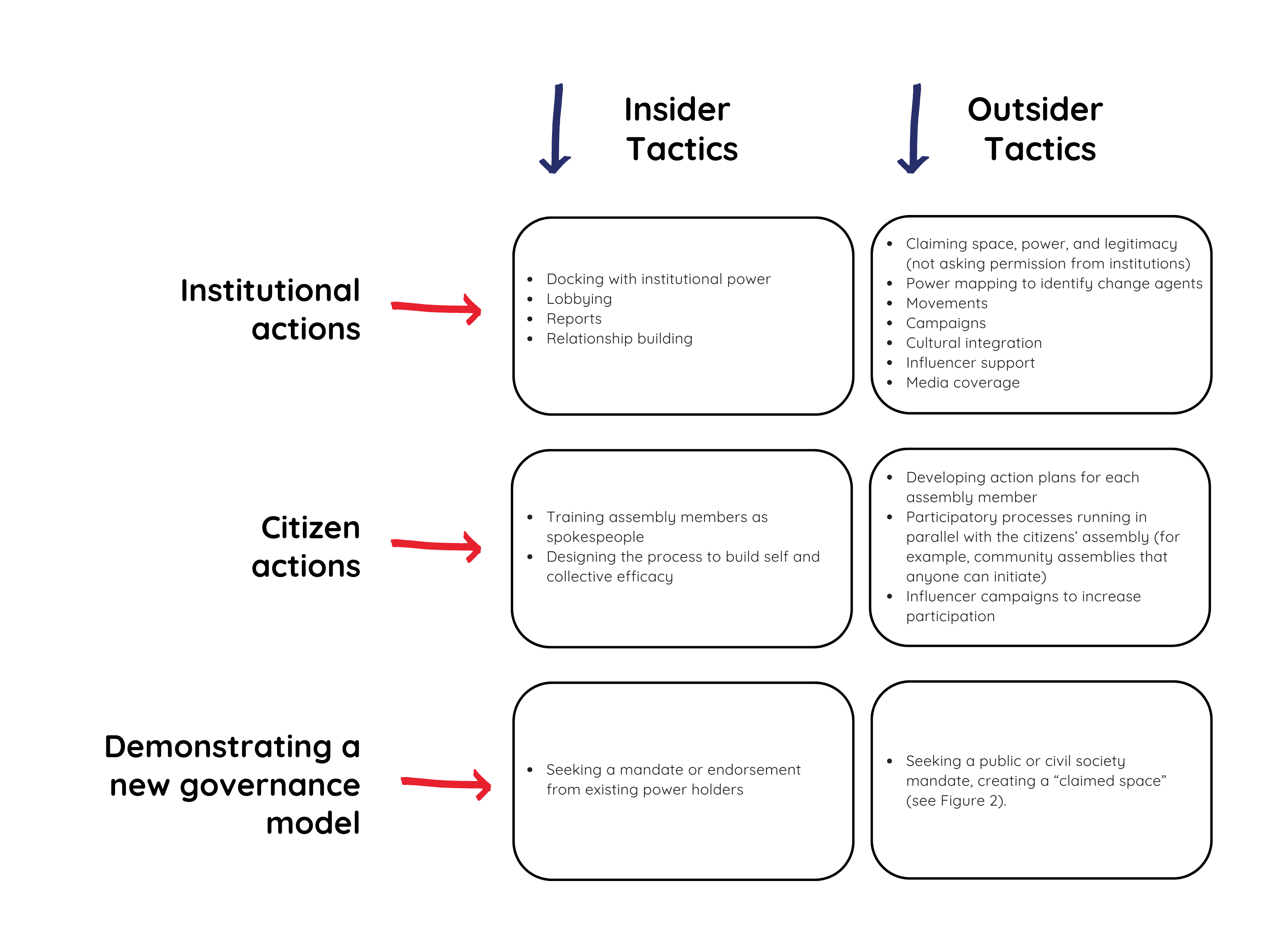

At the heart of a new theory of change for citizens’ assemblies must be developing a literacy of political power and of how change really happens. This involves having a full array of insider and outsider tactics for influence. Some are outlined initially in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Insider and outsider strategies to creating impact

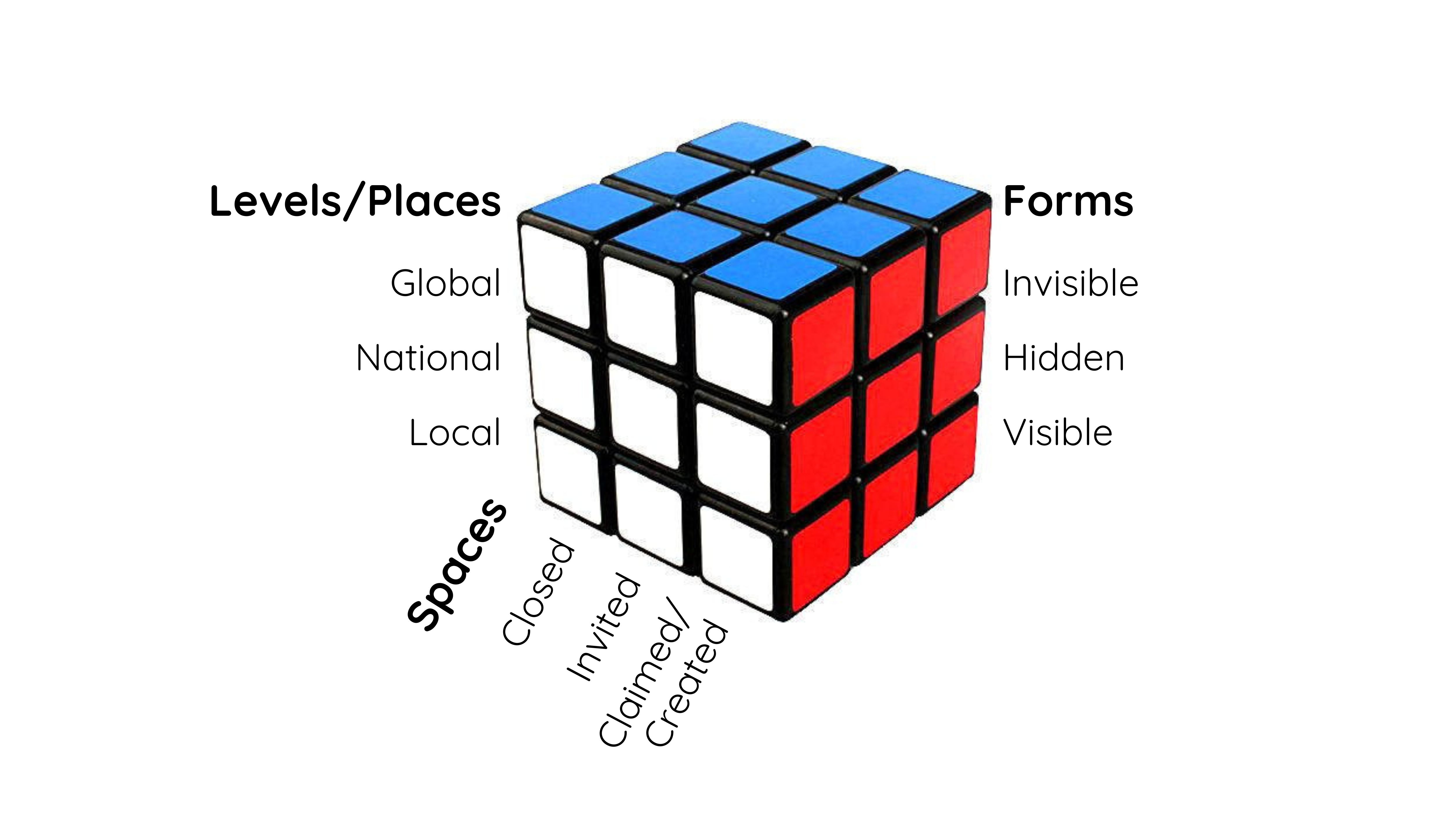

Many citizens’ assemblies focus only on the insider-institutional dimension. A new theory of change would cover all six dimensions. John Gaventa’s concept of a “power cube” is especially helpful when trying to develop a full understanding of the power dynamics that citizens’ assemblies operate across.

Figure 2: John Gaventa’s Power Cube

Traditionally citizens’ assemblies have been “invited” spaces, focusing on visible political power. By contrast, the Global Assembly and the Convention of the Future Armenian are spaces that have been “claimed” by civil society. However, it is necessary to take all forms of power seriously: visible power (for example, observable political or financial decision making), hidden power (for example, who sets the political agenda and who is invited in), invisible power (for example, the invisible psychological and ideological boundaries of participation and what is on the agenda).

There are different dimensions of power in citizens’ assemblies. Invisible power has profound implications for how citizens’ assemblies are run and even what they are. It affects what is considered “legitimate”, “radical”, or “unacceptable” in their framing and the information citizens consider. The same is the case in representative democracy where civil servants informing the politicians have often vast invisible power in precisely the same way. Some argue, for instance, that deliberative “mini-publics,” in their formulation and scope to date, have been complicit in maintaining the privileges of white western democratic theory and practice as well as the dependencies on systems of domination, racialization, and exploitation.

Relative to these broad notions of power, citizens’ assemblies are currently framed narrowly as specific event-based processes that usually inform a power holder. Instead, they need to be designed broadly as places to try out new and better governance chambers.

In his 2021 book Deliberative Democracy, Ian O’Flynn argues that a “narrow” focus on citizens’ assemblies is closing down debate on creating wider systems of deliberative democracy. Here, however, we use the term citizens’ assemblies as shorthand for wide-ranging reform of democratic systems. There is a real risk that a narrow focus could result in providing legitimacy for democratic systems that need fundamental reform. The move toward the institutionalization of permanent citizens’ assemblies is a case in point—it raises the question of whether to institutionalize creative and inclusive deliberative systems or narrowly defined adjuncts to existing governance chambers.

Widening Participation

A new theory of change for citizens’ assemblies also requires that the net of citizen participation needs to be widened considerably. That anyone can be selected for a citizens’ assembly through a civic lottery gives them legitimacy, but the small numbers involved, often just 150 members for countries with populations in the tens of millions, has given rise to criticism of exclusivity and lack of representation.

An emerging response to this question is the running of distributed events alongside or before citizens’ assemblies that can be run by anyone anywhere. For the recent People’s Assembly for Nature in the United Kingdom, such “conversations” formed “the first stage in creating the People’s Plan for Nature” that would inform the assembly. The Global Assembly for COP26 called ran “community assemblies” concurrently and beyond the core process. These provided a parallel DIY track using the same resources as the core process to increase the number of people who participated, and therefore to increase the associated benefits such as activation, solidarity, data generation, and political momentum. The community assemblies also took on board the principle that anyone who wanted to could participate, which is critical for wider political credibility.

Although such distributed events have obvious limitations, such as demographic representation and time for deliberation (they are usually much briefer than core processes of citizens’ assemblies), they have shown great promise. This did so as a mechanism to dramatically increase participation and to provide distributed citizens’ assembly infrastructure to support place-based (for example, in schools, communities, or places of worship) or stakeholder-based engagement (for example, with workers, experts, or industry).

These conditions in effect are creating a network of interconnected deliberative processes—some local, some national, some communities of interest. This is potentially a vast civic engagement infrastructure that anyone could plug into, forming a “deliberative system.”

In addition, citizens’ assemblies need to garner more public attention. It has long been established that a higher profile is likely to increase their impact. We have described elsewhere how high-profile ones can “defibrillate democracy.” We argued that “they can jolt the political system back to life, unblocking and expanding the arteries of political power.” In a 2021 survey, 70 percent of respondents in France said they knew about the Citizens Convention for Climate and 62 per cent said they supported the vast majority of its recommendations. This not only generated a powerful mandate for change but also sent a shock wave across the French political system. This could be described as “third generation mini-publics” where “a feedback loop or recursive dialogue between mini-publics and wider publics can be forged.”

The key to the success of France’s Citizens Convention for Climate was working with influencers who could use their social media following to penetrate new parts of the public discourse. For its part, the Global Assembly initiated a “cultural wave” track where cultural influencers generated creative responses to the project.

Getting Real About Citizens’ Assemblies

In 1999 Khalsa and Illig published the sales classic “Let’s get real or let’s not play”, arguing that business relationships are too often based on fear: buyers afraid of being manipulated and sellers afraid of not closing the deal. They argue that everyone “wins” when sellers “focus 100 percent on helping clients succeed” and instead of dancing around the truth show their hands up front.

The deliberative democracy movement needs to do the same. Its clients are citizens. Its business is to help citizens succeed in reclaiming their collective power to address the issues they want to address, whether existing power holders support them or not. The current wave of deliberative processes focuses on helping governments increase their legitimacy and pays too little attention to helping citizens achieve the change they want to see. These often top-down invited spaces end up depoliticizing citizen engagement at best, and at worst they provide legitimacy for governments that are in effect opposed to the changes citizens want.

The Buckminster Fuller quote “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete” has become popular in deliberative democracy circles. But, if the deliberative democracy movement is serious about how it can play a powerful role in rebooting how government works, it needs to act like it. This means ensuring every citizens’ assembly has a politically literate change strategy and the resources required to deliver it.

The Convention of the Future Armenian did this and resulted in a permanent Affiliation Network of influential people and organizations from across business, media, civil society, and politics with significant resources to take proposals forward. Perhaps the reason the organizers of the convention have taken seriously their ability to affect real change is that many Armenians believe their country faces immediate existential threats. Getting real about citizens’ assemblies means following this lead: recognizing the severity of the challenges people face and honoring this by putting in place systems that give people a real chance of affecting change.

Authors

Rich Wilson is the CEO of the Iswe Foundation. In 2004 he founded Involve, which under his leadership became a leading international centre for public participation research, innovation and policy-making. Since then he has been at the forefront of the new democracy movement; most recently co-founding the world’s first Global Citizens’ Assembly, Good Help, Funders Initiative for Civil Society. Rich is a trustee of the Local Trust. He is a senior policy adviser to the UK government and has been an adviser to the UNDP, WHO, OECD, EU and many national and local governments as well as NGOs and social movements. He started his career as an environmental economist working for SPRU, Exeter University and the Environment Council. He has written many policy reports, blogs on the Guardian, DeSmog, Carnegie Europe, New Internationalist, Open Democracy, is author of the ‘Anti Hero’ book and is a Clore Social Fellow.

Claire Mellier is knowledge and practice lead of Iswe Foundation. She co-initiated and organized the first Global Citizens’ Assembly on the climate and ecological crisis for COP26. Having delivered more than fifteen citizens’ deliberative processes on climate change and other topics, from the local to the global level, Claire is now exploring how to bring systems change into deliberative practice. Claire is an associate researcher at the Centre for Climate Change and Social Transformation (CAST) at Cardiff University, where she published a comparative analysis of the French and UK climate assemblies and a research briefing on systems change and citizens’ assemblies. She is on the Advisory Board of the International Panel on Social Progress.